Oh, how I cannot wait for the day that we have some money to do something as big as this.

[via Heather is Watching]

Oh, how I cannot wait for the day that we have some money to do something as big as this.

[via Heather is Watching]

I’m sure there will never be a lack of fence-related interventions, but this one in particular seemed worth posting. Small and simple, but the technique is so obvious and effective (if likely slow-going), I had to add it to our research archives.

[via Radical Cross Stitch]

Danielle and I spent the day at the University of Waterloo’s School of Architecture with the DodoLab team planning out a project that will take place in PEI near the end of August. Near the side of the building in this kind of walkway between two parts of the school, we saw this installation, completed by a 4th year architecture class.

The installation consists of a huge number of used coffee cups, chicken wire, and transplanted grasses and flowers. It undulates mildly until reaching the rail for the steps (in the right-side of the photo) where the planters climb the rail. The chicken wire is supported by other coffee cups and those cardboard heat-shields.

We didn’t get to speak to anyone who worked on this project, but it was another great reference for our own ongoing research.

A few people emailed us about this project (thanks for that!!) and I’ve since seen it on a number of other blogs, so it’s about time I got around to posting it on here. Green Sleeves by AT.AW uses a simple pattern to create planters from the layers of old wheat pasted posters.

The method is great—looking around the city (in this case, Toronto) and understanding the specificities that create opportunities for intervention in the city. The results seem to be a mixed bag, in terms of plants surviving longer than 24 hours; in some cases, the plants are stolen, dry out, or are torn down for more posters.

The project is generating a dialogue and for that it is successful and it may be able to translate better to a city where its illegal postering community is less vigilant.

[via Torontoist]

httpvh://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oL4LqJXur48&feature=player_embedded

Kind of strangely, I read about this project in the New Yorker and momentarily confused it with Canada’s Tree Museum, but ultimately thought it was worth noting given a recent conversation we had with Edwin who came by our Office Hours last week about a potential audio-based community project.

The video above describing the Holten’s project is kind of brutal (especially the soundtrack), but it gives a good idea of the way it works—acting as a kind of series of stops on a museum tour, with a variety of trees being the markers in each neighbourhood.

100 trees give voice to 100 perspectives featured in the Grand Concourse’s TREE MUSEUM. Irish artist Katie Holten created this public art project to celebrate the communities and ecosystems along this 100 year-old boulevard. Visitors can listen in on local stories and the intimate lives of trees offered by current and former residents: from beekeepers to rappers, historians to gardeners, school kids to scientists.

You can call 718-408-2501to access the audio guide.

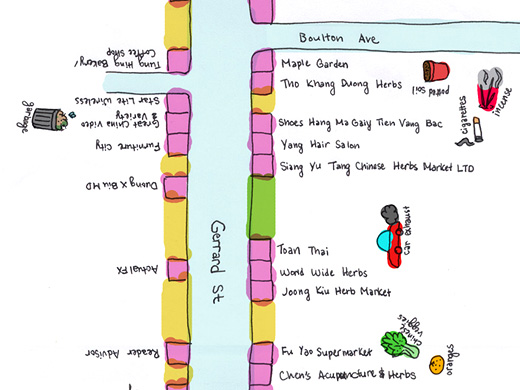

This is a small excerpt of a large map made by students in OCAD’s Cities for People summer workshop, depicting the East Chinatown neighbourhood, its businesses and their smells.

You should take a look at the larger map, which helps to demonstrate the potential in mapping outside of the continually pervasive Google Maps.

To take time to note a neighbourhood in this somewhat peculiar detail is an interestingly necessary method for interfacing with a place one might normally walk by, and in turn, of course, makes me eager to do the same somewhere around these parts.

[via Spacing]

From Green Museum:

One of the early pioneers of both the environmental art movement and Conceptual art, Agnes Denes brings her wide ranging interests in the physical and social sciences, mathematics, philosophy, linguistics, poetry and music to her delicate drawings, books and monumental artworks around the globe.

In 1982, she carried out what has become one of the best-known environmental art projects when she planted a two-acre field of wheat in a vacant lot in downtown Manhattan. Titled,Wheatfield — A Confrontation, the artwork yielded 1,000 lbs. of wheat in the middle of New York City to comment on “human values and misplaced priorities”. The harvested grain then traveled to 28 cities worldwide in “The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger” and was symbolically planted around the globe.

Imagine turning some the vast wasteland areas in the city (read any vacant big box store parking lot, Brighton Beach, EC Row Expressway) into a wheat field, or a meadow, or maybe more importantly, imagine having a year to make a project at this scale.

[via we make money not art]

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xZkf44jysYw

I like public art that does something. I like thinking about architectural works as art and about the potential for viewing city layouts as art and so, I like art that exists as something more than art.

Marcus Vergette‘s Time and Tide Bell is an early-warning system of sorts for the rising tide that will inevitably be the outcome of climate change. The work involves a newly invented bell form, which allows multiple tones to be struck in one structure, so as the tide rises, the bell’s clapper is moved to strike the bell. As the tide rises, the bell will ring more often, but will also become further submerged.

Watching the video above is kind of strange—it shows the first strike of the bell in the water. As people clap and as the bell rings again, it’s strange to think that there is art like this to be made. This bell appears to be the first of other bells that can be installed in other communities, and in some capacity, created with consultation with that community about the inscription on and tone of the bell.

Of course, I’ve now begun to wonder what a public work that would demarcate something very distinct to now, or very distinct to the place we’re heading that could be installed in Windsor. If there was something you could leave for someone to see well into a post-apocalyptic future, what would it be? I think I’d want to say, “I’m sorry.”

An random chance to catch up with Laura, Sam, and some other folks I hadn’t seen for a while turned into this quick intervention.

As part of their OH! C.N.A.P. fun, they had made a lot of bunting for another party they had to attend, but it seemed too great to not temporarily put up somewhere in the city. So, in the alley next to Phog, the bunting was quickly strung up with the help of staples (after some difficulties with the wind), and really was an great example of what’s possible with some paper, yarn, and a amazing group of people.

Check out more photos of the process at Laura and Sam‘s flickr sets, or check out Sam’s tutorial on making the bunting, should you be so inclined to take up a similar project.

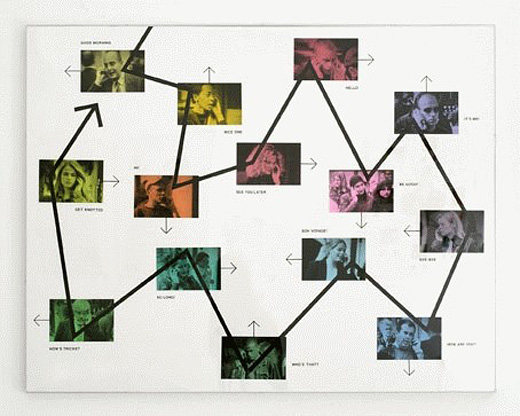

Stephen Willats worked in relation aesthetics when Nicolas Bourriaud was 15. Willats worked has often involved a collaborative process, where he engages with residents of public housing units for projects that can span years.

I’ve been re-reading Conversation Pieces by Grant H. Kester, spending some considerable time on the section about Willats. Kester frames Willats’ work around the processes embedded in the work, which often attempts to examine the potential for his collaborative partners exercising autonomy from the places in which they’re situated.

The problematic of the artist acting in the position that Willats often occupies, that is, in the position of coming into a socially or politically difficult situation from the outside and working to uncover things for the people who have lived those situations for much longer, is something to consider when working within a community as we do. This practice of course forces questions about the artist as a social worker. However, our interaction with a specific community has been somewhat limited (and on purpose). We’ve been able to maintain a level of activity based on our concerns and our experiences, which is empowering, but also potentially limiting, and yet I’m nervous to think about what it would mean to try to work more directly with other communities in the city.

I believe that there is a lot of room to work with communities in Windsor, but my hesitation to attempt to work in this mode of choosing a group to work with, and then creating a project around their concerns (or worse, our preconceived ideas of their concerns) isn’t necessarily relieved by looking at Willats’ work (and not that it has to be). I think his work is worth noting though, as it certainly made possible what it is we’re doing today.

Pictured above, “Around the Networks” by Stephen Willats from January 2002.